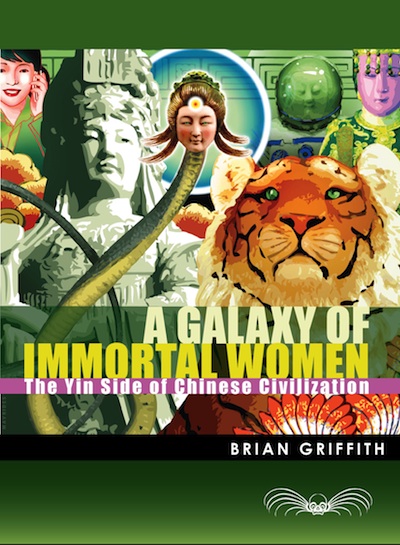

by Brian Griffith

China’s goddess cults are not normally classed as independent religions. They seem to be sub-sects of Daoism, Buddhism, or Confucianism. We could say that the goddess cults are women’s versions of these traditions. Some people call them “shadow religions.” Even today, the cults of women and goddesses are not classified as organized religions. They fall under the supposedly less important category of “popular religion.” Where men have usually dominated official religious institutions and professional priesthoods, the cults of women have spread informally among common people.

Official religion was almost all male, but popular religion was probably more influential.

Throughout China’s history, the legends, lives, and teachings of local wise women formed a counterculture to the values of warlords or patriarchs. And as in many countries, the traditional values of women and villagers bore little resemblance to those of their rulers. In a view from the rulers’ throne, the cults of peasants and women usually seemed unimportant. That’s one reason for the seemingly low profile of goddess religions. But there are additional reasons. Thomas Cleary lists a series of old sayings about the invisibility of real virtue in his Immortal Sisters: Secrets of Daoist Women:

“A skilled artisan leaves no traces.”

“She enters the water without making a ripple.”

“The skilled appear to have no abilities; the wise appear to be ignorant.” (1989, 6)

So when a mother teaches her children, it is best done when the children believe they did everything themselves. And the virtues celebrated in local goddess cults were often invisible to little emperors, or to sycophants who glorified tyrants.

At various times in the past, the rulers and state-backed priests treated goddess cults as subversive. The authorities occasionally tried to discredit female shamans or teachers as “stupid superstitious women.” They did it for roughly the same reasons that medieval churchmen tried to silence Europe’s wise women. But fortunately, the wise women of China never faced a seriously murderous extermination campaign. I suspect they were too popular, or the officials had too much respect their mothers’ values.

Over the centuries, a female-friendly counterculture evolved within Daoism, Confucianism, Buddhism, and village folklore. There are “yin” versions of all these traditions. For anyone interested in a culture of balance between male and female powers, the women’s religions offer a world of experience and insight. Their visions of life are strikingly different from what we find in most any official religion of the East, the West, or the Middle East.

In the West, of course, female deities are few and mostly long forgotten. Christianity has its thin line of sainted women from the Virgin Mary to Mother Teresa. But any goddess is an artifact from classical paganism. Islam has its cluster of holy women, especially from the faith’s early days. But a goddess would be a relic from the pre-Islamic “time of ignorance.” Judaism has its half-recalled mother of Israel, the spouse of Yahweh, the Matronit, the Shekhina, the Sophia, “the Discarded Cornerstone” (Patai, 1990, 128). But the goddesses of China are legion, and their cults have been popular from prehistoric times forward.